Food Production

Summary

This section proposes expanding disaster-resilient community gardens and improving their efficiency by reducing the land used by utilising creative methods of traditional farming and aeroponics. The purpose of the community gardens is to provide local food for preparation in the event of disasters and for local consumption.

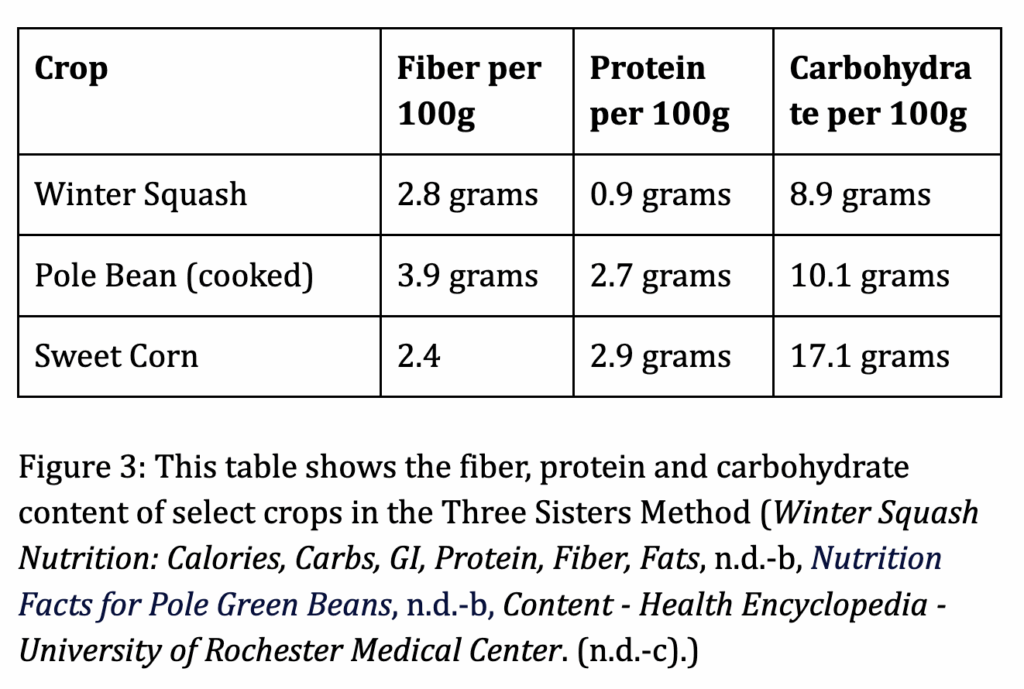

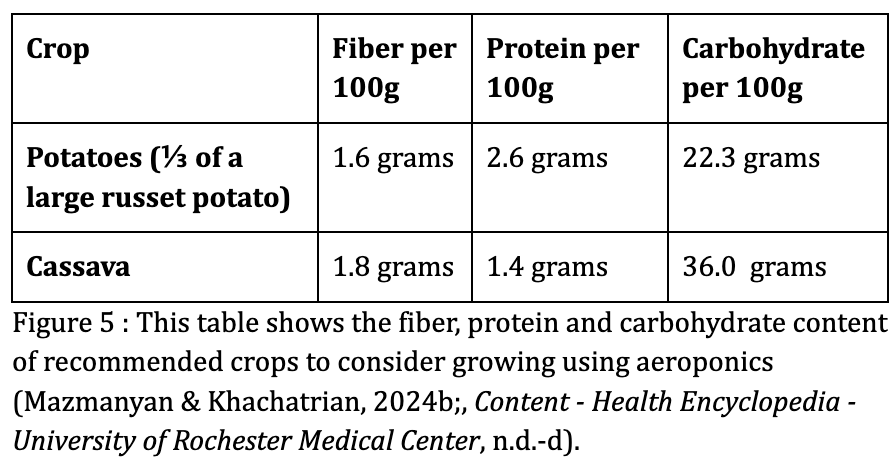

The main goal of the community gardens is to grow starchy, calorie-dense, filling produce that can meaningfully contribute to the food needs of the community, and thus make the community less reliant on expensive imports that may even become unavailable during disasters. To determine which crops to grow, we compared protein, fiber, and carbohydrate contents to determine levels of satiety, suppression of hunger after eating (Dahl, 2025).

When integrating local food production for the long-term solution, it needs to be considered more carefully for low-income areas since price differences between imported food and locally produced food are felt more deeply. For example, in lower-income areas, integrating local food production would have to happen over a longer span of time in order for the community to be able to afford the food being produced, compared to integrating local food production in a higher-income area (Belengrima 2025; Sep 2025, Release Tables: Food | FRED | St. Louis Fed, n.d.).

Importance of Increasing Local Food Production

This proposal’s goal is not to completely shift Puerto Rico’s food industry to local agriculture, as less than 1% of Puerto Rico’s current GDP comes from agriculture (Statista, 2025). Instead, its goal is to have reliable, delocalized sources of food in communities across Puerto Rico during disasters, and eventually provide a cheaper alternative to food imports in Puerto Rico (Background & Labor).

With only about 15% of food consumed in Puerto Rico being produced locally, the current system will not be able to sustain the population of about 3 million people for indefinite periods of time, until ports are fully operational from the impacts of hurricanes (U.S Census Bureau 2025; FEMA 2018).

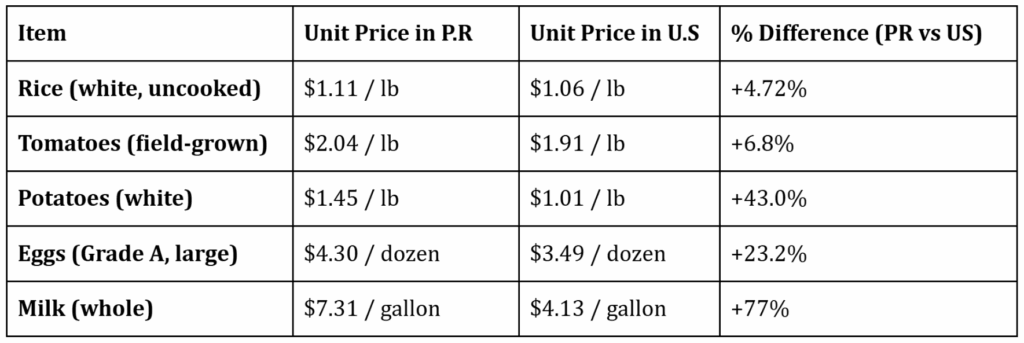

In comparison to mainland US grocery stores, Puerto Rican grocery prices are significantly higher across produce, poultry, and dairy products due to the added costs of shipping from the Jones Act (FRED 2025; Belengrima 2025; Grabow 2024). The graph below shows the price differences between a select group of products in Puerto Rican and mainland US grocery stores. The price estimates and distribution of locally grown produce are not explicitly recorded, so the table below assumes that the majority of the products are imported. While information on the price of local produce isn’t readily accessible, the cost of imports is a definite factor in the increased prices, a factor that can be eliminated through local production.

Figure 1: This table compares the cost of select grocery products in Puerto Rico and the costs of these products in the Mainland US (Belengrima 2025; Sep 2025, Release Tables: Food | FRED | St. Louis Fed, n.d.)

The increased price of imported foods can add a financial burden to locals. Integrating community gardens with resilience hubs would increase local food production and consequently diversify food sources while helping reduce over-dependence on imports. The proposed plan doesn’t guarantee price reductions in groceries, but offers an alternative source of food. Food production efforts are essential to Puerto Rico to allow the island to have more food stability (Background). The distribution of local food production should prioritize low-income areas since price differences between imported food and locally produced food are felt more deeply.

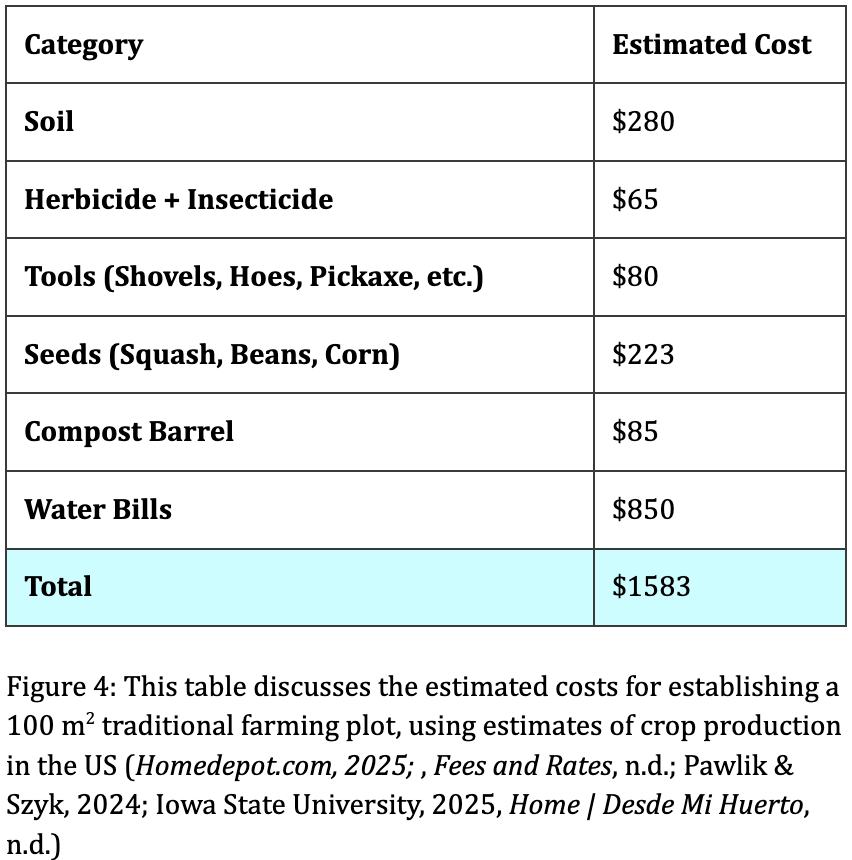

For community gardens, we propose makeshift aeroponics and traditional farming methods as potential methods to accommodate for limited land availability. The two methods can be used individually or in conjunction with one another.

Our proposal for the set-up and implementation of community gardens and aeroponics as well as our crop choices, is all centered around the daily nutritional requirements for a healthy and filling diet, which can be found below for reference.

Aeroponics is a soilless method of growing produce where plant roots are suspended in air. A nutrient solution is then delivered as mist to nourish and hydrate the plant, facilitating growth. (Overview | www.fao.org).

Potential Farming Methods

There are many ways to approach local production. By evaluating the potential farming methods that are suitable in Puerto Rico, two viable options are outlined: traditional farming and aeroponics. While other methods are also compatible with the region, our proposal finds both methods to have unique benefits for community needs. On a case-by-case basis, alternative methods should be explored using a similar approach as described below.

Traditional Farming

Traditional farming takes up many forms that all have different nuances. Broadly speaking, traditional farming can apply differently based on specific regional needs. We use traditional farming to refer to any form of soil farming. This can include large-scale plot farming or small-scale garden beds. There are also different methods of traditional farming, such as intercropping, agroforestry and the Three Sisters Method (Encyclopedia of Biodiversity, 2013). In this proposal, we recommend considering various scales of farming based on regional needs and capacity.

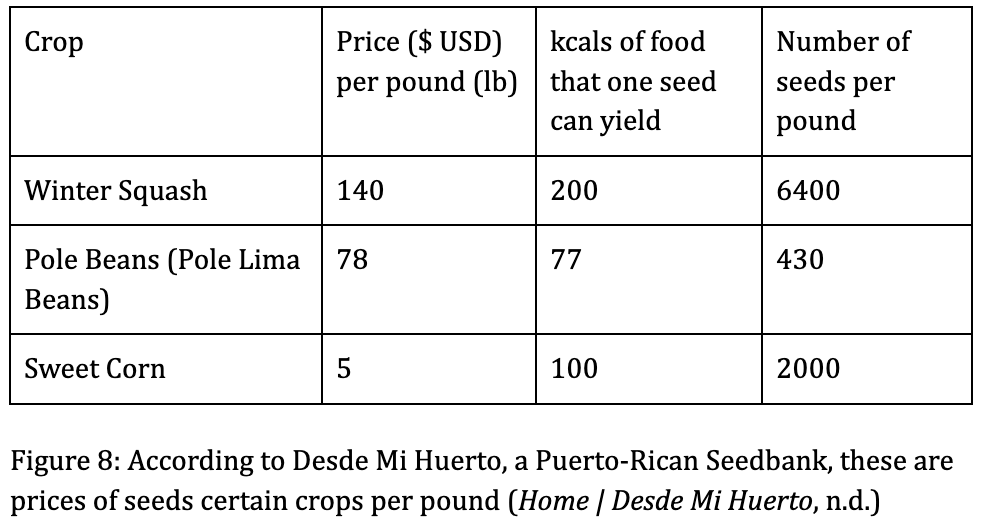

An example of traditional farming is the Three Sisters method, which is a planting method that grows squash, beans, and corn together to create a mutually beneficial growing environment. The commonly used and environmentally compatible breeds for the Three Sisters method are winter squash, pole beans, and sweet or dent corn. These breeds are currently grown in Puerto Rico, and are flexible for the different types of soil present in Puerto Rico (Towermarketing, 2021; Boeckmann, 2025). Other intercropping duos, such as plantains and tubers like sweet potatoes or eggplant, or a combination of cacao and bananas, should be considered. The Three Sisters Method is highlighted as an example because of its historical and cultural significance.

When these three plants are grown together in this method, they maximize the amount of calories (122,500 kcal) and protein (3.5kg) produced per 100 square meters for each growing season (Mt.Pleasant, 2016). This amounts to 245 meals consisting of 500 kcal. Similar intercropping methods can be calculated based on growing seasons and nutritional impact.

Aeroponics

Aeroponics can grow a range of nutritious foods, including potatoes, yams, carrots, tomatoes, beans, and leafy greens. More filling crops like potatoes and cassava should be prioritized using aeroponics. Other filling, starchy root crops like malanga (taro), and yautia, also grown in Puerto Rico, are also good candidates for aeroponic growth, and can be looked further into for each community garden (Selvaraj et al., 2019b).

According to ICAR and NASA case studies, aeroponic systems can yield up to 35% more vegetables than traditional methods, all while reducing pest exposure and the onset of disease. The closed-loop nature of aeroponic systems also helps maximize efficient water use and the production of nutrient-dense produce (Kirmani, 2025).

Building an Aeroponics System

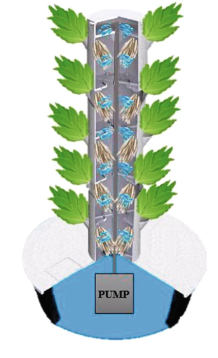

The essential components of the proposed aeroponic system include:

- A nutrient reservoir to store the nutrient solution required for growth

- A manual pump to mist water at different intervals of time

- A root chamber and plant support to hold the plants and suspend

their roots for misting

- Sufficient access to sunlight

- A mechanically-run drainage system

Community members interested and willing to volunteer to construct and maintain these aeroponic farms can acquire the required training and skillset through various resources such as online courses. For areas with less access to WIFI, hard copies of the online course material can be distributed. Another potential method of training can be agricultural programs in collaboration with universities. Ideally, partnerships with agricultural institutions can be used to develop specific aeroponic guidebooks based on environmental conditions could be valuable in achieving maximum efficiency and cost-effective aeroponics systems. An example of an ideal guidebook that can be referenced is Otazu’s guide in the International Potato Center: Aeroponics Potato Production Manual (Otazú & International Potato Center, 2010b).

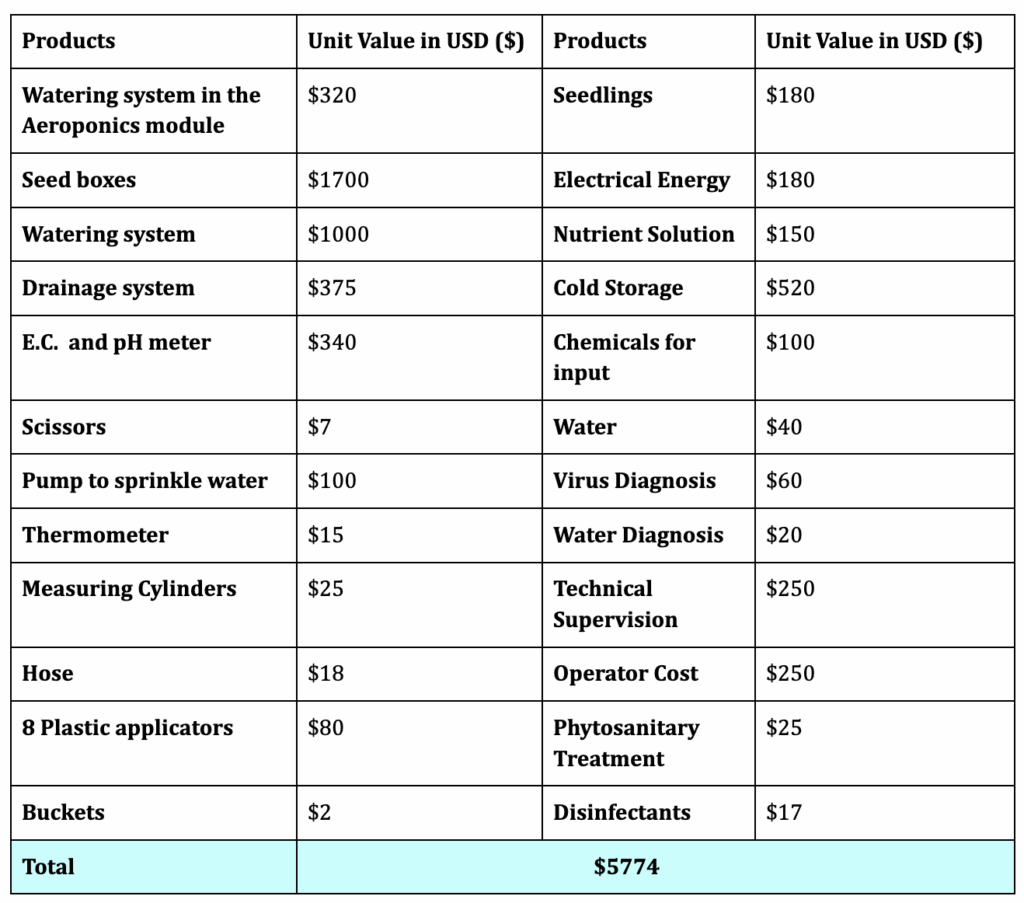

Similar costs are anticipated for the proposed makeshift aeroponic systems, but we also suggest modifying them per local considerations, specifically without the use of greenhouses. For instance, Puerto Rico struggles with an unreliable power grid, a problem that is further exacerbated by natural disasters. This necessitates establishing an aeroponics system that can run independently of electricity. Alongside manual maintenance and oversight on the plants’ hydration and progress, we also recommend mechanically-based nutrient and water delivery.

For instance, one study proposed that a vertical aeroponics tower pipe setup would allow gravity to propagate nutrients from the top and pass through all the plants on the way down, which would further reduce overall costs (Faisal et al., 2024).

While we noted that aeroponics usually has a significantly greater crop yield per square meter than traditional soil-based methods, another research study further analyzed how this crop yield varied with plant density. The study looked into specifically mini-tubers, which are small marble-sized potato tubers that can later grow into commercial potato crops for consumption. Using potato mini-tubers as the primary subject, researchers found that greater plant density correlated with fewer individual tubers per potato plant. However, they also found that a density of 200 plants per square meter maximized tuber yield per square meter, with some experiments showing a yield of over 3000 tubers per square meter (Çalışkan et al., 2020). This case study indicates both the potential of aeroponics for crop yield as well as regeneration, especially when addressing obstacles regarding seed shortages. Assuming an average tuber density, one can grow about 11 kg worth of potatoes per square meter, which yields 1100 kg per 100 square meters. Potatoes contain about 770 kcals per kg. Overall, a 100-square meter aeroponics potato farm has the potential to yield 847,000 kcals which is equivalent to about 1600 meals.

Addressing Seed Shortages

An important factor to consider with seed banks is the potential copyright issues associated with the sale of crops. The recommended course of action is to evaluate region needs based on community need and potential crop yield to evaluate percentage of locally produced crops sold in the resilience hubs. More specific intellectual property concerns for seed production and sales can be referred to by the Organic Seed Alliance (Organic Seed Alliance, 2025).

Aeroponics for Disaster Resillience

The great advantage of aeroponics is that they are often built in modules, which means that under the threat of a natural disaster, they can be easily deconstructed and stored at a safe location, then reconstructed again for use. Incorporating aeroponic food production as a part of resilience hubs also helps ensure regions of the island where imports are no longer accessible still have access to an independent food source, alongside the community garden. These aeroponics modules will be set up outside as their ability to be deconstructed and transported eliminates the necessity of a formal greenhouse. This also alleviates significant costs since greenhouses are often the most expensive part of conventional aeroponics systems (Faisal et al., 2024).

Considered Alternative Methods

Besides aeroponics and traditional farming, there are many other methods of farming or production that should be considered in Puerto Rico. In our specific proposal, we chose to prioritize traditional farming and aeroponics because they suited the general area of Puerto Rico the most, specifically reducing energy and water usage.

Indoor Vertical Farming

Indoor vertical farming was initially considered in the solution proposal, with the assumption that this method would be more disaster-resilient than traditional outdoor farming. However, during a conversation with Alex Borschow, a venture capitalist and investor focused on sustainable food systems, we learned that indoor vertical farming in Puerto Rico is not as disaster resilient because it is typically done in greenhouses, which don’t hold up well in hurricanes. The greenhouses are necessary in order to use sunlight to grow the plants, since artificial lighting is costly and subject to problems with power outages, which occur frequently. For some communities, this may still be a viable option, but for our proposal, it is considered less ideal than the prioritized methods.

Aquaponics

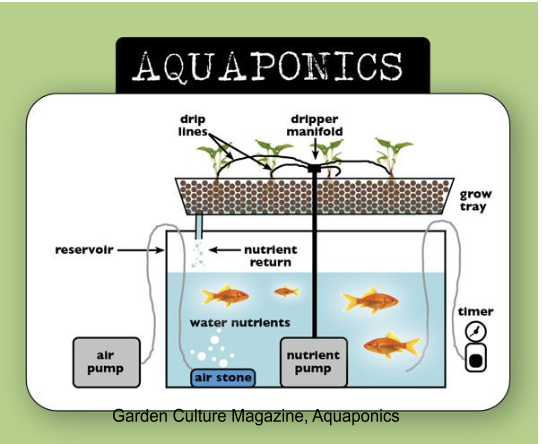

According to research biologist Carl Webster, aquaponics is a food production system that couples aquaculture (raising fish) and hydroponics (soilless plant farming). The method combines hydroponics with the cultivation of aquatic animals functions by raising aquatic animals such as fish, crayfish, snails, or prawns in tanks with hydroponics, whereby the nutrient-rich aquaculture water is fed to hydroponically grown plants. Fish waste, which is high in ammonia, is converted by beneficial bacteria into nitrates, a natural fertilizer. The plants then absorb these nitrates, purifying the water before it is returned to the fish tanks. This creates a balanced, symbiotic cycle that uses minimal water and avoids chemical fertilizers.

Implementing an aquaponics system in a region highly prone to natural disasters, such as hurricanes and tropical storms, presents significant vulnerabilities that make it less suitable than our proposed aeroponics and traditional farming approach.

In this case, we believe that aquaponics would be less suitable for the following reasons:

- Aquaponic systems are extremely vulnerable during disasters because they require constant electricity for circulation pumps and oxygenation.

- A prolonged power outage, common after a storm, can cause the entire fish population to die within hours from lack of oxygen and toxic waste buildup.

- Aquaponics structures, involving large tanks and plumbing, are heavy, bulky, and difficult to disassemble and store safely before a hurricane.

- These fixed structures are highly susceptible to physical damage, punctures, and ruptures from high winds and storm debris.

Hydroponics

Hydroponics is a method of growing plants using mineral nutrient solutions dissolved in water, instead of using soil. Plants are grown with their roots directly immersed in the nutrient solution or in an inert medium like rockwool or coco coir. Unlike aquaponics, hydroponics requires externally sourced chemical nutrient solutions to feed the plants, as it does not rely on fish waste. Various methods, such as deep water culture, nutrient film techniques, and drip systems, all circulate the solution to the plant roots (Resh, 2022).

Hydroponics, which involves growing plants without soil in nutrient-rich water, shares many of the vulnerabilities of aquaponics in disaster-prone areas.

This system would also not be ideal for the following reasons:

- It is entirely dependent on constant electrical power for running pumps and timers that circulate the nutrient solution.

- A power failure during a disaster halts circulation, causing stagnant water and rapid plant death due to oxygen deprivation at the roots.

- Hydroponic food production relies on a steady, external supply of chemical nutrient salts, which are vulnerable to import and supply chain disruptions following a disaster.

- The growing trays, channels, and reservoirs are often constructed from materials that are easily damaged or ruptured by high winds and storm debris.

Factors to Consider for Optimal Farming Method

To determine the priorities for individual community gardens, there are a few important considerations to make. Some examples of potential factors are the population and location of neighborhoods, environmental landscape, proximity to grocery stores, and major transport routes that can determine the ideal methods of production. Depending on the neighborhood, areas that are more disaster prone may prefer to implement aeroponics since it is less dependent on external environmental factors. Community definitions of success may vary based on community needs, which can range from land constraints to caloric needs. Based on the measure of success, communities can then determine the optimal farming method to achieve their goals.

A community’s decision of its optimal farming methods should help address the underlying community’s food insecurity needs. We propose that the use of aeroponics and/or traditional farming be executed in such a way that local production provides an alternative food source that can account for unprecedented food shortages.

Funding Sources

In addition to the main funding for the resilience hubs, we recommend exploring additional funding avenues for aeroponics and community gardens. For initial implementation, grants are often a feasible source of seed money. Applicable grants include the USDA’s Community Facilities and Seed Money’s annual grant program. These grants would get the community gardens up and running; however, for continual funding resources, grants will be less reliable. Reaching out to like-minded organizations, such as Just Mercy, an organization that built resilience hubs to assist during Hurricane Maria, could help fundraise or sponsor a few community gardens (‘Resilience Hubs’ in Puerto Rico Are Vital in the Wake of Hurricane Fiona, n.d.). Another likely organization that may be helpful to the cause is Feeding America’s Equity Impact Fund, which invests in initiatives across the US and Puerto Rico working to reduce food insecurity (Food Security Equity Impact Fund | Feeding America). Consulting local municipalities to get funding can be another effective method. There are organizations like El Depa dedicated to supporting community-responsive, market-focused strategies working to build food sovereignty (Equitable Food Oriented Development Case Study: El Departamento De La Comida, Puerto Rico – World Food Policy Center, 2024). The land for the community gardens themselves will be accounted for by the resilience hub size, so funding the construction of the community gardens and their maintenance will be the main priorities for the outlined funding sources.

Education

Agricultural and disaster education promotes long term food security through teaching self-sustaining farming practices and food preservation techniques. We propose an expansion of agricultural education to support the people of Puerto Rico in the movement towards a more sustainable future.

There are three main focuses for our proposal:

- Agricultural Education in Elementary Schools

- Community Education on Self-Sustaining Farming Practices

- Disaster Preparedness Education in Elementary Schools

These focuses will be expanded on in their respective sections along with a developed roadmap for a pilot program implementation. Through this proposal, we aim to increase the amount of agricultural and disaster education opportunities in Puerto Rico in order to decrease food insecurity. This proposal is targeted towards various organizations in Puerto Rico that we believe could implement the ideas and provide funding in the following ways:

Government:

- Puerto Rico Department of Education (DEPR)

- Curriculum implementation.

- Puerto Rico Emergency Management Agency (PREMA)

- Disaster resiliency curriculum development.

- U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA)

- Curriculum implementation.

- Offers funding opportunities and grants for agriculture in Puerto Rico.

- SARE (Sustainable Agriculture Research and Education)

- Funds projects focused on curriculum and educational development in agriculture and sustainability.

Nonprofits and Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs):

- Red Cross

- Funds and deliver programs focused on emergency preparedness

- El Josco Bravo

- Aids in offering agroecological trainings and courses in resilience hubs

- Plentitud PR

- Aids in offering agroecological workshops in resilience hubs

- Mano Amiga Program

- Provides grants to nonprofit organizations in Puerto Rico that focus on education, arts and culture, entrepreneurship, health, and environmental protection

Universities

- The University of Puerto Rico

- Aids in framing the pilot as a research project

- Aids in administering tests for pilot program data

- University of Puerto Rico at Mayagüez

- Partners with for agricultural extension focused within resilience hubs

Background and Overview

By increasing instruction in agriculture, we hope to increase awareness of the current state of Puerto Rican agriculture and encourage steps by citizens to create gardens and become more self-sustainable. While decreasing import reliance is a multi-faceted problem, we think that these educational initiatives will be a small and inexpensive step toward self-sufficiency, food security, and safety amidst disaster. Education in resilience and basic farming techniques is proportional to how self-sustaining Puerto Rico is.

Another problem that Puerto Rico faces is the lack of educational resources necessary for preparation for natural disasters, which are frequent on the island. A study done shows that only 41% of participants reported high pre-hurricane preparedness; 25% reported gaps (moderate/low availability) in information and 48% reported gaps in resources for hurricane preparedness (Joshipura, Martínez-Lozano et al., 2021). This gap in knowledge can impact how communities are affected by a disaster. By providing more education on ways to prepare for disasters, community members can be more equipped to respond in time. This will ensure that they know how to save food and water, where to go, and what resources are available to them.

To support the people of Puerto Rico and provide more educational resources, we are proposing implementing both an agricultural and disaster focused curriculum in elementary schools. We recommend a focus on elementary schools based on the fact that childhood is an important time for learning and cognitive development. The results from a study done on disaster resilience show that the best approach to educate disaster resilience response is the integration into school curricula. This study was done for disaster resilience education, but this result can be generalized to integrating agricultural education in school curriculum (Fu & Zhang, 2024).

We are proposing a pilot program in randomized schools across Puerto Rico where we incorporate agricultural education and disaster preparedness education in schools. Our proposal includes collecting data on the amount that students have learned in a school year through tests and surveys. Because a pilot program is instrumental to our proposal, we have sectioned out a roadmap for implementation.

While education for elementary school students is important for the youth and future generations, we also recommend agriculture-focused training sessions for the general public. To do this we propose that the Department of Education partners with established NGOs, university programs that hold courses on agricultural education, and resilience hubs to conduct general training. This ensures that the knowledge is shared within the community by experienced community members.

Exposing Elementary School Students to Agricultural Education

One underlying issue behind extreme import dependence is the lack of interest in agricultural focused jobs, as only 4% of farmers in Puerto Rico are under the age of 35 (USDA, 2022). The goal of the curriculum initiative is to educate students about the importance of farming and provide examples of career fields in this area. Since the focus is elementary school education, the priority is in raising awareness for farming and planting the seed of interest early. Professors at the University of Buffalo and Tufts proved this strategy to be an inexpensive way to foster critical skills in the youth that can help them transform the food systems in their nations through their research in SAI’s (school-based agroecological initiatives) (Ramos-Gerena & Bezares, 2023).

Leaving the program, we want students to be well equipped to start their own garden, help their parents to do so as well, and have an understanding of the possibilities of farming careers in the future. Thus, the curriculum would be broken into a few main parts: introduction to agriculture, basic farming knowledge, hands on experience, and agricultural jobs. These lessons can be molded to fit the context of different schools, but we recommend they be integrated into science classes. For schools where this wouldn’t be compatible, they can be provided as an afterschool program. Each section will consist of a few lessons administered in schools, with the hands-on experience taking place in community gardens and the career section involving field trips.

Agricultural Education Curriculum

Community Self Sustaining Farming Practices

As a response to a post-Hurricane Maria agricultural landscape, the agroecology movement has picked up steam within young Puerto Rican farmers (Lakhani, 2021). This system emphasizes sustainable agricultural practices that are guided by the conditions of the local landscape and preserves the regulating services of the natural environment, such as erosion control. However, the majority of farmers in Puerto Rico are older and have been farming for over a decade thus limiting their exposure to agroecology as a viable method of farming (USDA, 2022). A study done on farmer’s adaptation strategies after Hurricane Maria showed that education was positively linked to the adoption of ecological transition and natural design processes (Rodríguez-Cruz et al., 2021).

We propose coordinating established organizations in agroecology and agricultural extension, such as El Josco Bravo, Plentitud PR, and the Agricultural Extension Service at UPRM, to offer training, courses, and seminars in resilience hubs regarding agroecology. Each of these organizations have already done the legwork to establish relevant curriculum for agroecology and related subjects aimed at small farmers in Puerto Rico, however, their reach remains limited. For example, The El Josco Bravo School of Agroecology offers specialized courses in 11 towns across the island (El Josco Bravo. (n.d.)). El Josco Bravo. https://www.eljoscobravo.org/. We aim to connect these organizations to physical locations through resilience hubs to host their seminars and give them a physical platform in which they can reach more people.

Disaster Preparedness Education and Community Trust

Puerto Rico faces challenges with members of the community being uninformed about how to prepare for a natural disaster. In order to combat this information gap we propose the incorporation of disaster preparedness education into elementary schools’ curriculums.

One study found that 40% of the papers included in the study indicated that the best approach to educate about disaster response and resilience is the integration of disaster prevention education into school curricula (Fu & Zhang, 2024).. Because of this, we are proposing a school curriculum for disaster preparedness. This ensures that everyone is exposed to disaster-preparedness education through the school system.

Our proposed curriculum is designed to improve disaster preparedness by teaching individuals how to plan effectively and how to respond during an emergency. The program aims to decrease the proportion of community members who feel unprepared and to ensure that families are equipped with the necessary resources.

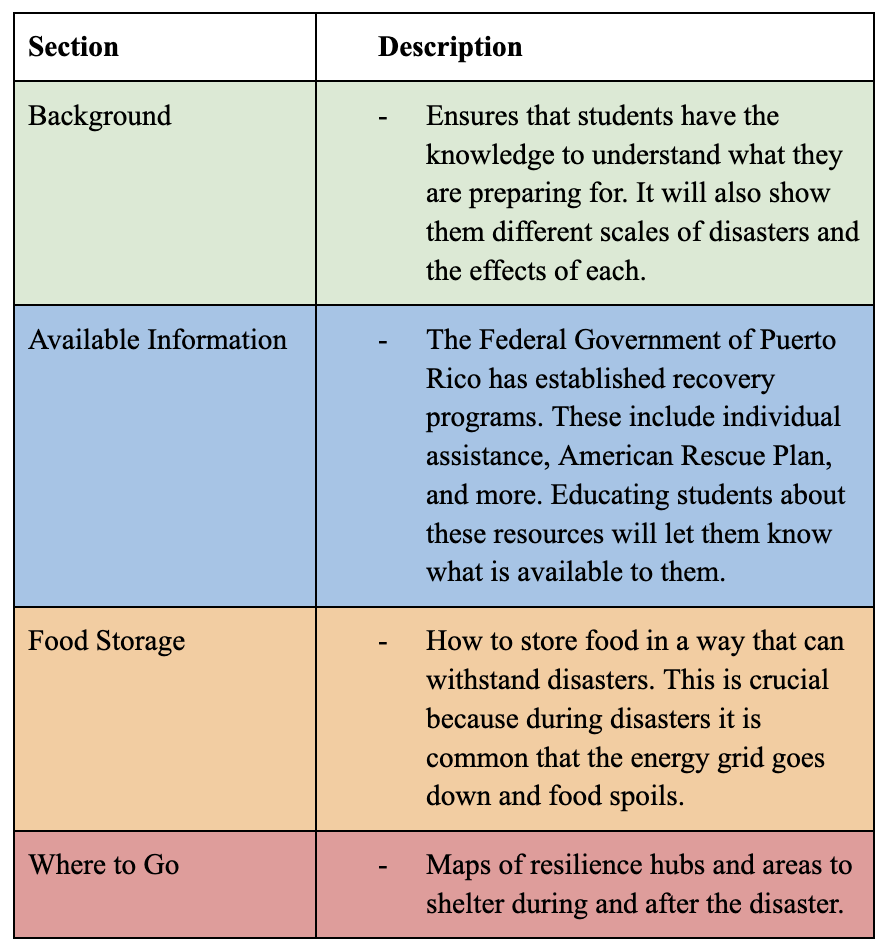

The curriculum we are proposing is made up of 4 main topics: Background, Available Information, Food Storage, and Where to Go.

Disaster Preparedness Curriculum

Curriculum and Pilot Program Implementation

To incorporate these curriculums, we propose a pilot program for randomized elementary schools over Puerto Rico. Starting with a pilot program ensures that resources are not wasted on an ineffective program. If it is successful, it can also make a case for further funding efforts.

To accurately assess the impact of each pilot program and prevent overlap in results, we recommend the implementation of disaster preparedness and agriculture education in separate elementary schools. This separation ensures that any observed effects can be attributed specifically to the program delivered at each school.

In order to successfully implement the pilot program and curriculum, we have developed a roadmap to make this process easier and cost-effective. The funding sources mentioned will be expanded on further in the funding section.

Phase 1: Planning

This phase aims at developing the framework for the project.

It will entail:

- Form a steering committee.

- Members from Puerto Rico Department of Education, Department of Agriculture of Puerto Rico, University of Puerto Rico – Mayagüez, Plentitud PR, El Josco Bravo.

- Identify pilot schools– randomized across the island.

- Define program goals, success metrics, and evaluation plan.

- Secure initial funding.

Phase 2: Curriculum Development

This phase will deal with developing the curriculum with the needed resources.

It will entail:

- Draft curriculum modules.

- Ensure content aligns with local context and standards.

- Develop teacher guides and training materials.

Phase 3: Teacher Training and Pilot Program

This phase focuses on preparing the teachers and starting the pilot program.

It will entail:

- Train teachers with online modules.

- Provide classroom materials and resources.

- Launch curriculum in selected schools.

- Collect initial data on students’ knowledge.

Phase 4: Delivery and Monitoring:

This phase will work on teaching the curriculum and keeping up with data.

It will entail:

- Administer the curriculum.

- Monitor student engagement and learning.

Phase 5: Evaluation and Refinement

This phase will assess the effectiveness of the program and make necessary changes.

It will entail:

- Administer final tests and surveys.

- Analyze changes in student knowledge.

- Prepare a report for improvement.

- Decide whether to expand, adjust, or end the program.

Phase 6: Scaling up

This phase depends on if the program is deemed successful and will be expanded.

- Train additional teachers.

- Secure long-term funding.

Funding

Our proposal relies on multiple pathways of funding. For flexibility and affordability, we have compiled a list of various options along with what they could be sources of funding for.

Goverment Funding

- U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA)

- Southern SARE (SSARE) Professional Development Program: offers grants focused on education, training, and conservation for producers and educators in Puerto Rico.

- In 2025, the SSARE Administrative Council funded 18 projects totaling $386,238 (Puerto Rico – SARE Southern, 2025).

- Southern SARE On-Farm Research Grant: funds on-farm research and training in conservation and sustainable practices.

- In 2025, Puerto Rico received $42,473 allocated for On-Farm Research Grant (Puerto Rico – SARE Southern, 2025)

Research Grants

University of Puerto Rico: The University of Puerto Rico has at least $150 million in endowment, internal funding (FIPI), as well as external funding from groups such as the NIH. These can aid with implementation, funding, and evaluation of these programs. (UPR Endowment Fund – Portal De Donaciones Del Recinto De Río Piedras UPR, n.d.)

Nonprofits and Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs)

Red Cross: Funds and delivers programs focused on emergency preparedness through a $200,000 donation from LUMA to the American Red Cross of Puerto Rico (LUMA, 2022).

Production References

Belengrima. (2025, September 30). Cost of living in Puerto Rico: Food, transport, and more. Holafly. https://esim.holafly.com/finance/cost-living-puerto-rico/

Boeckmann, C. (2025, July 23). The three sisters: corn, beans, and squash. Almanac.com. https://www.almanac.com/content/three-sisters-corn-bean-and-squash

Bringing New Markets to Puerto Rico’s Producers. (2025, January 21). Usda.gov. https://www.usda.gov/about-usda/news/blog/bringing-new-markets-puerto-ricos-producers

Çalışkan, M. E., Yavuz, C., Yağız, A. K., Demirel, U., & Çalışkan, S. (2020). Comparison of aeroponics and conventional potato mini tuber production systems at different plant densities. Potato Research, 64(1), 41–53. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11540-020-09463-z

Census Reporter. (n.d.-a). Census profile: Canas Urbano barrio, Ponce Municipio, PR. https://censusreporter.org/profiles/06000US7211312355-canas-urbano-barrio-ponce-municipio-pr/

Census Reporter. (n.d.). Census profile: Cordillera barrio, Ciales Municipio, PR. https://censusreporter.org/profiles/06000US7203920568-cordillera-barrio-ciales-municipio-pr/

Center, H. R. R. (2025, July 10). The inequities in food assistance programs in Puerto Rico. HRRC. https://www.humanrightsresearch.org/post/the-inequities-in-food-assistance-programs-in-puerto-rico

Content – Health Encyclopedia – University of Rochester Medical Center. (n.d.-c). https://www.urmc.rochester.edu/encyclopedia/content?contenttypeid=76&contentid=11900-2

Content – Health Encyclopedia – University of Rochester Medical Center. (n.d.-c). https://www.urmc.rochester.edu/encyclopedia/content?contenttypeid=76&contentid=11353-3

Dahl, C. D. &. H. A. (2025, February 18). Macronutrients 101: What to know about protein, carbs and fats. MD Anderson Cancer Center. https://www.madanderson.org/cancerwise/macronutrients-101–what-to-know-about-protein–carbs-and-fats.h00-159774078.html

Drip Irrigation Tubing. (n.d.). The Home Depot. Retrieved November 20, 2025, from https://www.homedepot.com/b/Outdoors-Garden-Center-Watering-Irrigation-Drip-Irrigation-Drip-Irrigation-Tubing/N-5yc1vZckrg

eeg2@illinois.edu. (2017, January 15). Agriculture in Puerto Rico – A Brief analysis | BioMASS Lab – University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. https://publish.illinois.edu/lfr/2017/01/15/agriculture-in-puerto-rico-a-brief-analysis/

Encyclopedia of Biodiversity. (2013). Academic Press.

Equitable Food Oriented Development Case Study: El Departamento de la Comida, Puerto Rico – World Food Policy Center. (2024, February 14). World Food Policy Center. https://wfpc.sanford.duke.edu/reports/el-departamento-de-la-comida-puerto-rico/

Faisal, A., Rajashekar, V., Biswal, P., Mukherjee, A., & Bhowmick, G. D. (2024). Advancing Agriculture with Aeroponics: A Critical Review of Methods, Benefits, and Limitations. Encyclopedia of Sustainability Science and Technology Series, 311–322. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-0716-3993-1_16

Fees and rates. (n.d.). San Juan Water District. https://www.sjwd.org/fees-and-rates

FEMA. (2018). 2017 Hurricane Season FEMA After-Action Report. https://www.fema.gov/sites/default/files/2020-08/fema_hurricane-season-after-action-report_2017.pdf

Food Security Equity Impact Fund | Feeding America. (n.d.). Feeding America. https://www.feedingamerica.org/our-work/equity-impact-fund

Go Green Aquaponics. (2025). How to protect your aquaponics system during a power failure. https://gogreenaquaponics.com/blogs/news/how-to-protect-your-aquaponics-system-during-power-failure

Grabow, C. (2024, July). New Paper Examines Jones Act’s Cost to Puerto Rico [Review of New Paper Examines Jones Act’s Cost to Puerto Rico]. Cato Institute. https://www.cato.org/blog/new-paper-examines-jones-acts-cost-puerto-rico

Homedepot.com, 2025, www.homedepot.com/p/40-lb-Top-Soil-71140180/100355705.

Home | Desde mi huerto. (n.d.). Desde Mi Huerto. https://www.desdemihuerto.com/en

Iowa State University. (2025). Estimated costs of crop production in Iowa–2025. In Ag Decision Maker. https://www.extension.iastate.edu/agdm/crops/pdf/a1-20.pdf

Jagdish. (2018, December 5). Aeroponic Farming Cost, Business Plan Guide | Agri Farming. Agri Farming. https://www.agrifarming.in/aeroponic-farming-cost-business-plan-guide

Jones Jr., J.B. (2004). Hydroponics: A Practical Guide for the Soilless Grower (2nd ed.). CRC Press. https://doi.org/10.1201/9780849331671

Karimanzira, D. and Rauschenbach, T. (2018) Optimal Utilization of Renewable Energy in Aquaponic Systems. Energy and Power Engineering, 10, 279-300. https://doi.org/10.4236/epe.2018.106018

Kirmani, S. N., Gulzar, M., Bhat, S. A., & Raja, W. H. (2025). Aeroponics: An Innovative Technique for Production of Vegetable Crops. In Aeroponics: An Innovative Technique for Production of Vegetable Crops (pp. 1–16). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-99-0862-2_12-1

Król, M. (2023, April 11). Growing nutritious food through aquaponics | Garden Culture Magazine. Garden Culture Magazine. https://gardenculturemagazine.com/growing-nutritious-food-through-aquaponics/

Matos-Moreno, A., Santos-Lozada, A. R., Mehta, N., De Leon, C. F. M., Lê-Scherban, F., & De Lima Friche, A. A. (2021). Migration is the Driving Force of Rapid Aging in Puerto Rico: A Research Brief. Population Research and Policy Review, 41(3), 801–810. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11113-021-09683-2

Mazmanyan, V., & Khachatrian, E. (2024, August 22). Cassava nutrition: calories, carbs, GI, protein, fiber, fats. Food Struct. https://foodstruct.com/food/cassava

MDPI. (2023). Sustainability analysis of aquaponic systems (energy and infrastructure vulnerabilities). https://www.mdpi.com/2073-4441/15/24/4310

Mph, K. M. Z. R. L. (2024, December 12). How many calories should you eat? WebMD. https://www.webmd.com/diet/calories-chart

Mt.Pleasant, J. (2016). Food Yields and Nutrient Analyses of the Three Sisters: A Haudenosaunee Cropping System. Ethnobiology Letters, 7(1). https://doi.org/10.14237/ebl.7.1.2016.721

Nutrition facts for Pole green beans. (n.d.). https://www.myfooddiary.com/foods/7778277/pole-green-beans

Organic Seed Alliance. (2025, November 6). About OSA – Organic Seed Alliance. https://seedalliance.org/about-osa/

Otazú, V. & International Potato Center. (2010). Manual on quality seed potato production using aeroponics. International Potato Center (CIP). https://cipotato.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/005447.pdf

Overview | www.fao.org. (n.d.). https://www.fao.org/agroecology/overview/en/

Pawlik, K., & Szyk, B. (2024, June 14). Soil calculator. Omni Calculator. https://www.omnicalculator.com/biology/soil

Puerto Rico Arable land, percent of land area – data, chart | TheGlobalEconomy.com. (n.d.). TheGlobalEconomy.com. https://www.theglobaleconomy.com/Puerto-Rico/arable_land_percent/

Puerto Rico Agriculture Results from the 2022 Puerto Rico Census of Agriculture Highlights.

(n.d.).https://www.nass.usda.gov/Publications/Highlights/2024/Census-of-Ag-22_HL_PuertoRico.pdf

‘Resilience Hubs’ in Puerto Rico are vital in the wake of Hurricane Fiona. (n.d.). Mercy Corps. https://www.mercycorps.org/blog/resilience-hubs-puerto-rico-vital

Resh, H. (2022). Hydroponic food production: A definitive guidebook for the advanced home gardener and the commercial hydroponic grower (10th ed.). CRC Press. https://doi.org/10.1201/9781003133254

Rodríguez-Cruz, L. A. (2025, September 25). How Puerto Rico’s Seed Banks Are Boosting Food Sovereignty. Proximate. https://www.proximate.press/latest-stories/without-seeds-there-is-no-food-seed-banks-boost-agriculture-in-puerto-rico#:~:text=Seed%20shortages%20cntribute%20to%20food,environmental%20conservation%20in%20Puerto%20Rico.

Selvaraj, M. G., Montoya-P, M. E., Atanbori, J., French, A. P., & Pridmore, T. (2019). A low-cost aeroponic phenotyping system for storage root development: unravelling the below-ground secrets of cassava (Manihot esculenta). Plant Methods, 15(1), 131. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13007-019-0517-6

Sep 2025, Release tables: Food | FRED | St. Louis Fed. (n.d.). https://fred.stlouisfed.org/release/tables?eid=816251&rid=454&utm

Statista. (2025, June 26). Distribution of gross domestic product (GDP) across economic sectors Puerto Rico 2023. https://www.statist.com/statistics/397789/puerto-rico-gdp-distribution-across-economic-sectors/?srsltid=AfmBOoq4W9vDmYBXYcLWwz8M10aaJnmMZxkfxLbo41aA1y5VEH2Itwy

Towermarketing. (2021, May 7). Grow your own three sisters garden – Stauffers of Kissel Hill. Stauffers of Kissel Hill. https://www.skh.com//blog/learn-how-to-grow-your-own-three-sisters-garden-corn-beans-squash/

Tunio, M. H., Gao, J., Shaikh, S. A., Lakhiar, I. A., Qureshi, W. A., Solangi, K. A., & Chandio, F. A. (2020). Potato production in aeroponics: An emerging food growing system in sustainable agriculture for food security. In Jiangsu University & Jiangsu University, CHILEAN JOURNAL OF AGRICULTURAL RESEARCH (Vol. 80, Issue 1) [Journal-article]. Jiangsu University. https://doi.org/10.4067/S0718-58392020000100118

University of Miami Inter-American Law Review | Journals | University of Miami Law School. (n.d.). https://repository.law.miami.edu/umialr/

US Census Bureau. (2025, September 25). Population and housing unit estimates. Census.gov. https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/popest.html

USDA. (n.d.). Nutritional goals for each age/sex group used in assessing adequacy of USDA Food Patterns at various calorie levels. https://health.gov/sites/default/files/2019-09/Appendix-E3-1-Table-A4.pdf

“What is aquaponics?” 26 July 2011. HowStuffWorks.com. https://home.howstuffworks.com/lawn-garden/professional-landscaping/what-is-aquaponics.htm?s1sid=iqgbbnix5abpewe48aq286q4&srch_tag=thvt7oagmtyehlqncmydsrgsb4tjjm4q

Winter squash nutrition: calories, carbs, GI, protein, fiber, fats. (n.d.). Food Struct. https://foodstruct.com/food/winter-squash

Zorrilla, C. D. (2017). The View from Puerto Rico — Hurricane Maria and Its Aftermath. New England Journal of Medicine, 377(19), 1801–1803. https://doi.org/10.1056/Nejmp1713196

Education Refrences

El Josco Bravo. (n.d.). El Josco Bravo. https://www.eljoscobravo.org/

Fu, Q., & Zhang, X. (2024). Promoting community resilience through disaster education: Review of community-based interventions with a focus on teacher resilience and well-being.19(1). e0296393–e0296393. PLOS ONE. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0296393

Joshipura, K. J., Martínez-Lozano, M., Ríos-Jiménez, P. I., Camacho-Monclova, D. M., Noboa-Ramos, C., Alvarado-González, G. A., & Lowe, S. R. (2021). Preparedness, hurricanes Irma and Maria, and impact on health in Puerto Rico. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 67. 102657. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2021.102657

Lakhani, N. (2021, December 23). “An act of rebellion: the young farmers revolutionizing Puerto Rico’s agriculture”. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2021/dec/23/puerto-rico-agroecology-farmers

Luma. (2022, July 20). LUMA and the American Red Cross, Puerto Rico Chapter, announce continued partnership to provide assistance and education programs in communities across Puerto Rico and launch Disaster Relief Initiative. LUMA. https://lumapr.com/news/luma-and-the-american-red-cross-puerto-rico-chapter-announce-continued-partnership-to-provide-assistance-and-education-programs-in-communities-across-puerto-rico-and-launch-disaster-relief-initiativ/?lang=en

Ramos-Gerena, C., & Bezares, N. (2023, June 26). Expanding Agroecology in Puerto Rico’s K-12 Public Schools: Indicators for Sustainable Continuation. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8111753

Rodríguez-Cruz, Luis Alexis, et al. (July 2021). Puerto Rican Farmers’ Obstacles toward Recovery and Adaptation Strategies after Hurricane Maria: A Mixed-Methods Approach to Understanding Adaptive Capacity. Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems, vol. 5, 5. https://doi.org/10.3389/fsufs.2021.662918.

Saavedra-Lugo, J., & Hernandez-Aquino, B. (2025). Determination of the Profile of the Agricultural Education Teachers of Puerto Rico Aimed at Identifying Needs to Establish a Professional Development Plan. Journal of Agricultural Education 66(1), 25. https://doi.org/10.5032/jae.v66i1.2896

SARE (n.d.). Puerto Rico grants list. https://projects.sare.org/state-fact-sheets/?st=PR&action=sfs&submit=Go&script_id=sfs

SARE (2025, June 26). Puerto Rico – SARE Southern. SARE Southern. https://southern.sare.org/sare-in-your-state/puerto-rico/

UPR Endowment Fund – Portal de Donaciones del Recinto de Río Piedras UPR. (n.d.). https://donaciones.uprrp.edu/en/endowment-fund/.

USDA (n.d.). Puerto Rico Agriculture Results from the 2022 Puerto Rico Census of Agriculture Highlights. https://www.nass.usda.gov/Publications/Highlights/2024/Census-of-Ag-22_HL_PuertoRico.pdf