Disaster Resiliency

General/Background Information

Puerto Rico is among one of the locations most impacted by natural disasters. Its geographic location in the Caribbean Sea, between the Caribbean and North American tectonic plates, causes the island to experience frequent hurricanes and earthquakes. While initiatives exist to help the island with food insecurity after said disasters, they face issues with outreach and effectiveness, leaving many without proper access to food.

Proposed Solution

To address the issues, we propose to create a plan for these hubs to distribute more nutritious food prior to disasters. Therefore, this section discusses the disaster resiliency side of resilience hubs and proposes emergency food packets to decrease food insecurity during disasters.

Current Initiatives and Shortcomings

To determine the issues of interest and devise our proposed solution, we examined case studies of previous efforts from communities and organizations elsewhere to assist the territory after disasters. We focused on both successes and shortcomings of tested initiatives.

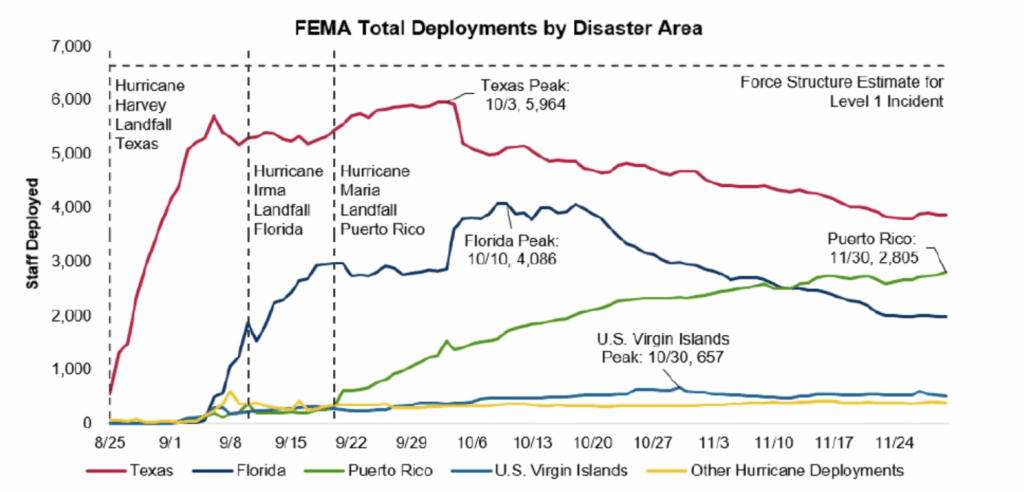

We found that past efforts were limited in outreach and took a significant amount of time to fully take effect. For example, a study by Rodríguez Cruz & Niles (2018) following Hurricane Maria found that even a month after the storm, 59% of those surveyed were still facing challenges acquiring food. Other vital resources are also missing immediately following a disaster. An estimated 44% of Puerto Rico still didn’t have access to drinking water for over a week following Hurricane Maria (Rocha, 2017). This can be attributed to less aid received by Puerto Rico following disasters, compared to areas like Texas and Florida (Willison et al., 2021). While our proposed emergency packets won’t last for a month, they are for the immediate aftermath of a disaster. Other parts of our proposal, such as education and community supermarkets, aim to address the long-term aftermath of the storm.

(FEMA, 2018). A graph of how quickly deployments were made for Harvey, Irma, and Maria.

Implementation and Cost

Expanding resilience hubs and its functions for emergency food packets and disaster resilient measures, our proposal aims to address the issues of limited access to food and water, as well as lack of aid to the island.

Additionally, a study found that the food distributed in Puerto Rico during natural disasters does not have sufficient nutritional content. A study found that of 107 unique food items, 41% were snacks and sweets, and 13%, 4%, 13%, and 7% were fruits, vegetables, proteins, and grains, respectively. Fifty-eight percent of all foods were low in fiber (≤1 g); 46% included high amounts of sodium, saturated fats, or added sugars (≥20% daily value) (Colón-Ramos, 2019). These meal packages complied with the Dietary Guidelines for Americans food group recommendations, but they exceeded upper daily limits for sodium, saturated fat, or added sugars (Colón-Ramos, 2019).

The unhealthy content in the emergency food packets that currently exist is an issue because following natural disasters, they are a primary source of nutrients to those impacted. In order to improve the health of those in need during disasters, we propose that these packages be improved by replacing unhealthy content with the following items:

- Fresh produce, particularly vegetables (potatoes, cassava, carrots). These would come from community gardens grown in resilience hubs, when available. Providing fresh produce comes with challenges of refrigeration; because of this, municipalities need to consider whether or not they aim to include fresh produce during the design and planning of the hub.

- Dried beans, lentils, and corn, which would come from “pantries” of resilience hubs. This would serve as a source of protein.

- Sources of carbohydrates, such as pasta, and rice

- Canned goods such as meat, vegetables, and fish. These would also come from resilience hub “pantries”

- Chlorine tablets, to purify water. These would have to be purchased and stocked by resilience hubs.

- Basic first aid supplies. These would be stocked in resilience hubs beforehand.

Canned goods and dry foods are included in the current emergency food packages since they are shelf stable and don’t necessarily need electricity to be safely eaten. However, we propose additional items for nutrition.

To determine effective strategies, we conducted a case study of Vibrant Hawai’i: a non-profit organization that operates resilience hubs in Hawai’i (Vibrant Hawai’i, n.d.). This organization distributes food, offers training in lifesaving skills like CPR, as well as food preservation skills like freeze drying. In 2020, their facilities assisted 41,733 households and 108,214 individuals. (Vibrant Hawai’i, 2023)

Both Puerto Rico and Hawai’i are tropical islands that experience natural disasters frequently. Due to this similarity in climate, we consider basing the success of Vibrant Hawai’i’s response to those in Puerto Rico. From this case study, we learned about their methods of distributing food and emergency supplies, which include partnering with other organizations and focusing on community-based distribution events. Partnering with other groups helps them share resources and get a larger knowledge base to create a more streamlined response system. This has proved useful in Hawai’i, so we propose a similar strategy in Puerto Rico. However, demographic differences, among other differences between the islands, will alter the implementation strategies in Puerto Rico.

Distribution of Emergency Food Packets:

Proposed resilience hub locations have been selected in various locations throughout Puerto Rico based on multiple factors that influence social vulnerability, which is elaborated in depth in the Locations section. We plan for emergency food packets to be distributed at the same sites as these proposed hubs, because these communities are the most vulnerable; the supplies in these packets are stocked by these hubs.

Our goal is for enough food aid to be distributed to the entire community surrounding these resilience hubs in particular, so that they will have around 3-4 days worth of food, as the first 72 hours are especially critical, elaborated on in the Resilience Hub definition lower on this page.

Our example locations are Canas Urbano and Cordillera. These locations encompass two separate scenarios, with Canas Urbano being in an urban setting and aiming to serve 15,000 people, and Cordillera being established in a rural context and serving 2,000 people.

Emergency food packets will be packaged and distributed by the same people working in these resilience hubs, workers from existing initiatives, and recruited volunteers. These will ideally be distributed a few days before disaster, when people are still able to travel short distances safely.

Budget:

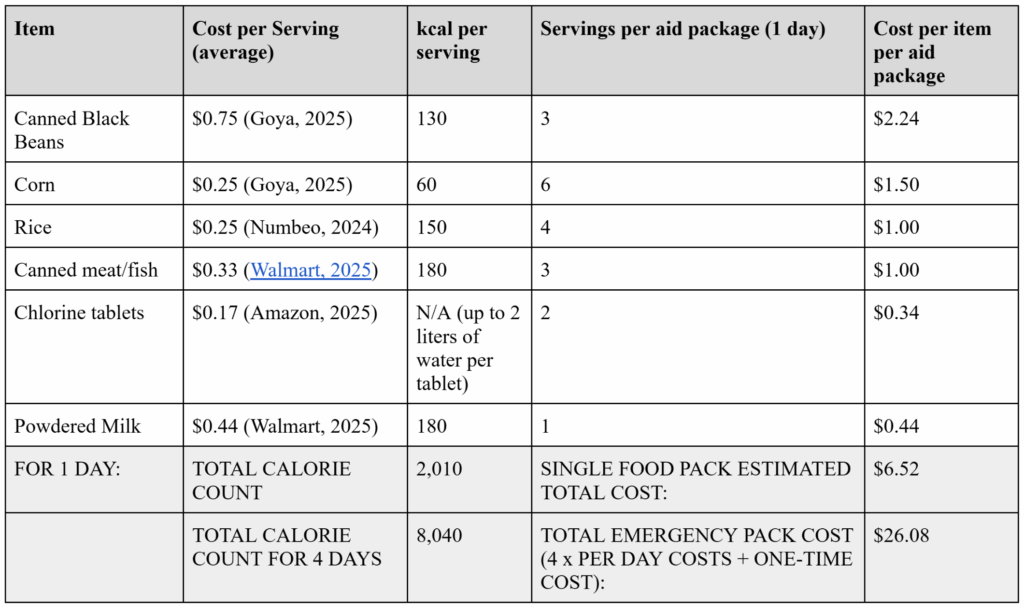

We calculated the budget that would be necessary to distribute enough food for this population during a disaster. These costs are based on the cost of each food item being packaged, and the quantity that would be distributed.

As mentioned in our previous section, most items packaged will have already been kept in stock by resilience hubs, except for chlorine tablets and first aid. Commercial chlorine tablets cost about $17 to purify 50 gallons of water (Amazon, n.d.). Each person consumes about 5 cups of water a day (CDC, 2024). In order to supply 17,000 people enough clean water for a week, about $14,000 would need to be allocated for chlorine tablets in total for everyone. Since this will be spread out over multiple resilience hubs that will each be able to support around 2,000 people, each resilience hub would need about $1,600 worth of water purification supplies.

As for the general cost for a single emergency pack, including the market cost of goods that will be supplied or grown by resilience hubs, the total cost for a pack that will feed one person for 4 days is estimated from this breakdown:

This example emergency pack adequately hits the 2,000 calorie/day suggestion.

This table shows the ranges in prices for different items. The makeup of a person’s diet in a certain region could change and would affect the makeup and cost of these packets.

The cost for produce will vary depending on the item and method used. Click here to read more about the infrastructure costs associated with fresh produce.

Since these example locations cover different conditions, this gives an indicator as to a range of estimated costs for emergency food packets. Considering the factors discussed in implementation, Cordillera might need less emergency packs since storm surges wouldn’t damage the area as much as Canas Urbano. Resilience hubs in Cordillera would prioritize day-to-day supply of food through community supermarkets while resilience hubs in Canas Urbano would prioritize disaster resiliency strategies such as these emergency packets.

This is an estimate on the higher side because we expect buying in bulk will lower unit costs and therefore total costs.

To gauge the cost of a single resilience hub, there was a case conducted on the City of Orlando. We chose to analyze the City of Orlando because they also face similar natural disasters to Puerto Rico, and because of their transparency with hub funding. The City of Orlando converted six community centers into resilience hubs with emergency power supplies with a block grant of $2,850,000 from the state government, which funded renovations including electrical upgrades, improved HVAC, and additional generators (City of Orlando, n.d.). This would be $475,000 per hub, assuming equal distribution of funds across each center. This provides a baseline to compare upgrading an old building to building an entirely new building. As discussed in the following secion, the cost vs. benefit of renovating old buildings compared to building new facilities is something to take into consideration. Each has its pros and cons which is discussed in the aforementioned section.

Community Supermarkets

What are Resilience Hubs?

A definition of what a resilience hub is can be found here.

Our goal with the resilience hubs is twofold:

- Maintain a steady food supply for the local community through disasters.

- Increase food security in nondisaster times through community produce.

Point 1 is discussed in Disaster Resiliency. To address point 2, we will discuss improving food sovereignty in nondisaster times by implementing community supermarkets through these resilience hubs.

The purpose of a resilience hub is to work in conjunction with existing solutions for food insecurity and disaster relief. For example, larger structures like schools are often converted to shelters during disasters to house people in a safer, stronger space during storms. Davis et al. investigates the widespread closure of schools in Puerto Rico and the potential to repurpose these abandoned spaces into vibrant community spaces, especially in times of natural disaster (Davis et. al., 2023).

A potential option for some communities would be to look into open and unused spaces. They could convert some of these abandoned and otherwise unused spaces that already have existing infrastructure into resilience hubs by adding assets such as backup power, emergency food and water supply, internet, and community gardens. This will help fill the voids left by these closures while also providing a community resource- not just day-to-day, but also during times of natural disaster. This could reduce the costs that would arise from constructing entirely new buildings. However, using abandoned buildings would force the resilience hubs to build operations from the ground up. These operations would include connecting with already established community kitchens, local farmers, businesses, community leaders, and more. This would be a major drawback if the entity implementing these resilience hubs does not already have these connections.

If this drawback is too large, then integrating into existing networks of food banks and community kitchens offer a level of existing infrastructure and are already integrated into communities. Being able to utilize pre-established networks would make it easier to effectively integrate resilience hubs within communities. Potential tradeoffs would include higher costs of either building infrastructure from the ground up or expanding the existing infrastructure.

Community Supermarkets

Resilience hubs will have two models of operation because they are intended to function both in times of disaster and in day-to-day community life. During disaster times, this will consist of distributing emergency food packets. Other functions are described in Disaster Resiliency. During day-to-day operations they are intended to be general community supermarkets, which will be detailed in this section.

Other resources should be included to ensure the safety of a local population during a disaster. A radio/telecommunications device should be accessible with additional batteries so that remote areas can stay informed. Physical maps, an offline GIS system, or another type of navigation system that doesn’t rely on the internet is also recommended (American Academy of Pediatrics, 2007).

Specifics and Considerations

In the short-term, food that would be sold or distributed at these resilience hubs would come from either local food producers or imported. In the long-term, food supplied in these resilience hubs would come from local farmers as referenced in Food Production. Further development of this proposal could expand on collaboration between local farmers, truck drivers, distributors, and resilience hubs.

Comedores Sociales is a grassroots organization that aims to improve food sovereignty – a community’s ability supply food– by establishing different initiatives within their communities. One of these initiatives is Súper Market Solidario, a cooperative supermarket that provides a set amount of food for those under the poverty line at either no charge or for volunteer hours. Súper Market Solidario also sells food for the general public at lower prices compared to Puerto Rican standard prices (Comedores Sociales de Puerto Rico, n.d.). This community supermarket has a “solidarity shelf” where residents can choose a limited amount of preserved food and basic hygienic products (Rivera Rivera, 2024).

(Rivera Rivera, 2024) A man stands in front of Súper Market Solidario’s solidarity shelf, able to pick a few items of preserved foods for free.

This structure of either paying or volunteering for products can help the resilience hub retain revenue. In the case the proposed community supermarket isn’t profitable, funding could be taken from many different sources to supplement revenue. Súper Market Solidario relies on collections, donations, profits, and federal/state grants to sustain the operation. For more information on funding resilience hubs, see our Funding page. If interested, organizations similar to Súper Market Solidario is a good model for operations, costs, and impacts of a cooperative supermarket.

There should be a consideration that some of the offered food could be stored for some period of time outside of freezers or refrigerators. Puerto Rican residents say “apagones” (blackouts) can affect areas of the island for days or weeks even without a major storm (Martinez, 2025). Per our Location page, you can see that remote areas take much longer to recover power after a disaster, with a clear correlation between population density and recovery time (Roman et al., 2019). Therefore, it’s important to ensure that these foods are shelf stable.

Powering a Hub

Power is usually restored to urban areas the fastest (per our Location page), resilience hubs in urban areas would have a need for an independent power source for extended periods of time during blackouts. Thus, resilience hubs in rural areas would likely need a more robust power supply to be able to refrigerate remaining fresh food while power is restored.

Although recommending emergency power sources is out of our scope, we recommend investigation of solar power so that hubs are able to stay powered even during blackouts. Some organizations in Puerto Rico such as Casa Pueblo already use off-grid solar power combined with batteries to serve as backup power (Casa Pueblo, n.d.). Additionally, Mercy Corp’s resilience hubs are also outfitted with solar panels (‘Resilience Hubs’, 2022). We recommend making resilience hubs better equipped with independent sources of power and batteries so it can effectively store fresh food even during blackouts.

Labor

Resilience hubs of this magnitude will require labor to operate. In order to construct the hubs, paid independent contractors will need to be included in the costs of a resilience hub. The extent to how much construction will have to be done will affect the scale of the operation. If merely renovating an old building, then the scale would be much smaller than if the resilience hub would be built from the ground up. A resilience hub would need to hire people and put employees on a payroll. These costs would need to be considered depending on the region as well as the scale of the operation. For further information about potential sources of funding for labor, please go to the Funding tab.

We realize that using volunteers primarily won’t be able to sustain the resilience hub. However, to minimize some operating expenditures and maximize community engagement we expect that these resilience hubs aim to utilize as many volunteers as possible, as exemplified by Vibrant Hawaii’s Resilience Hub network on the island of Hawai’i (Vibrant Hawaii, 2022). Following Super Solidario’s framework, volunteers could be sourced from either people buying food through volunteer hours or general volunteers. Using data on labor demographics, these resilience hubs could be placed in areas of high unemployment. By targeting areas of high unemployment, resilience hubs would offer a place of employment and further boost the local economy. Additionally, more people would be available to work in these resilience hubs. Education can help encourage more workers in these regions to consider agriculture. Therefore these resilience hubs could become a source of employment as well as a place for low-cost food and more. Volunteers would contribute through tasks including taking inventory of each resilience hub, organizing the distribution of supplies in emergency situations, and helping to maintain the community garden. As elaborated in (long term education), volunteers could also offer training on first aid, agriculture, and resilience either in the resilience hubs or in local schools.

Disaster Resiliency References

Amazon. (2025). Aquatabs 49mg Water Purification Tablets (100 Pack). Water Filtration System for Hiking, Backpacking, Camping, Emergencies, Survival, and Home-Use. Easy to Use Treatment and Disinfection. Amazon. https://a.co/d/0SNxCpZ

CDC. (2024). Fast Facts: Data on water consumption. Nutrition. https://www.cdc.gov/nutrition/php/data-research/fast-facts-water-consumption.html

Chopel, A. (2024). Getting Federal Money to Communities: A Story from Puerto Rico. Nonprofit Quarterly. https://nonprofitquarterly.org/getting-federal-money-to-communities-a-story-from-puerto-rico/

City of Orlando. (n.d.). Transforming community centers into resilience hubs. https://www.orlando.gov/Our-Government/Orlando-plans-for-a-future-ready-city/Transforming-Community-Centers-into-Resilience-Hubs

Collins, J., Polen, A., Dunn, E., Maas, L., Ackerson, E., Valmond, J., Morales, E., & Colón-Burgos, D. (2022). Hurricane Hazards, Evacuations, and Sheltering: Evacuation Decision-Making in the prevaccine era of the COVID-19 pandemic in the PRVI region. Weather Climate and Society, 14(2), 451–466. https://doi.org/10.1175/wcas-d-21-0134.1

Colón-Ramos, U., Roess, A. A., Robien, K., Marghella, P. D., Waldman, R. J., & Merrigan, K. A. (2019). Foods Distributed During Federal Disaster Relief Response in Puerto Rico After Hurricane María Did Not Fully Meet Federal Nutrition Recommendations. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, 119(11), 1903–1915. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jand.2019.03.015

Goya. (n.d.). Pinto Beans. Shop Goya. https://shop.goya.com/products/goya-pinto-beans-16-oz-bag?variant=41791027282113&country=US¤cy=USD&utm_medium=product_sync&utm_source=google&utm_content=sag_organic&utm_campaign=sag_organic

Kishore, N., Marqués, D., Mahmud, A., Kiang, M. V., Rodriguez, I., Fuller, A., Ebner, P., Sorensen, C., Racy, F., Lemery, J., Maas, L., Leaning, J., Irizarry, R. A., Balsari, S., & Buckee, C. O. (2018). Mortality in Puerto Rico after Hurricane Maria. New England Journal of Medicine, 379(2), 162–170. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmsa1803972

Mark, J., De Angel Sola, D., Rosario-Matos, N., & Wang, L. (2024). Post-disaster food insecurity: Hurricane Maria as a case study. The Journal of Climate Change and Health, 21, 100363. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joclim.2024.100363

Mark. (2024). Climate Education: Centering Communities for Climate Resilience in the Caribbean. Global Washington. https://globalwa.org/2024/09/climate-education-centering-communities-for-climate-resilience-in-the-caribbean/

Mercy Corps. (2022). ‘Resilience Hubs’ in Puerto Rico are vital in the wake of Hurricane Fiona. Mercy Corps. https://www.mercycorps.org/blog/resilience-hubs-puerto-rico-vital

Mercy Corps. (2024). 2024 FINANCIAL STATEMENT SUMMARY. In Mercy Corps Consolidated Operations [Financial statement]. https://www.mercycorps.org/sites/default/files/2025-03/2024-financial-statement-summary.pdf

Numbeo. (n.d.). Cost of living in Puerto Rico. Prices in Puerto Rico. https://www.numbeo.com/cost-of-living/country_result.jsp?country=Puerto+Rico

Palmer, A. (2024). Five Puerto Rico communities inaugurate energy resilience hubs. Interstate Renewable Energy Council (IREC). https://irecusa.org/blog/local-energy-climate-solutions/five-puerto-rico-communities-inaugurate-energy-resilience-hubs

Reveron-Arias, C. (2018). Annual report. Puerto Rico Rise Up. https://www.puertoricoriseup.org/annual-report/

Reveron-Arias, C. (2019). Annual report. Puerto Rico Rise Up. https://www.puertoricoriseup.org/annual-report-2019/

Reveron-Arias, C. (n.d.). Alimentos para Mi Gente. Puerto Rico Rise Up. https://www.puertoricoriseup.org/alimentos-para-mi-gente/

Rice, white, long-grain, regular, cooked, 1 cup | University Hospitals. (2024). Uhhospitals.org. https://www.uhhospitals.org/health-information/health-and-wellness-library/article/nutritionfacts-v1/rice-white-long-grain-regular-cooked-1-cup

Rocha, V. (2017). Getting drinking water to more in Puerto Rico brings challenges. CNN. https://www.cnn.com/2017/09/28/us/puerto-rico-water-supply

Traylor, J. (2020). Signal found: Mercy Corps & community WiFi. Mercy Corps. https://www.mercycorps.org/blog/signal-found-community-wifi

TRIDGE. (n.d.). Fresh Cassava price in Puerto Rico | Tridge. Tridge. https://dir.tridge.com/prices/fresh-cassava/PR

U.S. Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), Puerto Rico Emergency Management Agency (PREMA), Banco de Alimentos Puerto Rico—Puerto Rico’s Food Bank, Unidos por Puerto Rico, The World Central Kitchen, & Food Cities, 2022. (2022). TACTICS TO TRY FOR EMERGENCY FOOD PLANNING: Planning for Catastrophic Events with Lessons Learned from Puerto Rico. In Tactics to Try series. https://foodfoundation.org.uk/sites/default/files/2021-12/T2T%20Puerto%20Rico.pdf

Velázquez Estrada, A.L., (2018). Perfil del Migrante, 2016. San Juan, Puerto Rico: Instituto de Estadísticas de Puerto Rico. Retrieved from https://estadisticas.pr/files/Publicaciones/PM_2016_1.pdf

Vibrant Hawai’i. (2021). 2020 Vibrant Hawai’i Annual Report. Issuu. https://issuu.com/vibranthawaii/docs/2020vhimpact

Vibrant Hawai’i. (2024). 2023 Kaukau 4 Keiki Impact Report. Issuu. https://issuu.com/vibranthawaii/docs/k4k2023

Vibrant Hawai’i. (2024). Vibrant Hawaiʻi Annual Report. Issuu. https://issuu.com/vibranthawaii/docs/2023annualreport

Walmart. (n.d). Johnson & Johnson First Aid To Go Portable Mini Travel Kit, 12 pieces. https://www.walmart.com/ip/Johnson-Johnson-First-Aid-To-Go-Portable-Mini-Travel-Kit-12-pieces/10801432?classType=VARIANT&athbdg=L1102

Walmart. Palm Corned Beef with Juices, 11.5 oz Can. (n.d.). https://www.walmart.com/ip/Palm-Corned-Beef-with-Juices-11-5-oz-Can/37620750?wl13=3114&selectedSellerId=0&wmlspartner=wlpa&sid=05387c58-3c0e-4303-b23c-a81cdf910c2d

Willison, C. E., Singer, P. M., Creary, M. S., Vaziri, S., Stott, J., & Greer, S. L. (2021). How do you solve a problem like Maria? The politics of disaster response in Puerto Rico, Florida and Texas. World Medical & Health Policy, 14(3), 490–506. https://doi.org/10.1002/wmh3.476

Community Supermarkets References

Mercy Corps. (n.d). RESILIENCE HUBS action and evidence. https://www.mercycorps.org/sites/default/files/2019-11/Mercy%20Corps%20Resilience%20Global%20Capacity%20Statement.pdf

Signal found: Mercy Corps & community WiFi. (n.d., September 30). Mercy Corps. https://www.mercycorps.org/blog/signal-found-community-wifi

‘Resilience Hubs’ in Puerto Rico are vital in the wake of Hurricane Fiona. (202t2, October 10). Mercy Corps. https://www.mercycorps.org/blog/resilience-hubs-puerto-rico-vital

Comedores Sociales de Puerto Rico. (n.d.). ¡La solidaridad alimenta a Puerto Rico!. https://www.comedoressocialespr.org/

ChatGPT. (n.d.). Used for citation generator and assistance in idea synthesis.

Casa Pueblo. (n.d.). Solar. CasaPueblo.org. https://casapueblo.org/category/solar/

Davis, J., Reyes, M., Abrogar, J., Bourgoin, J., Brown, M., Kellum, E., Polito, F., & Jiusto, S. (2023). Puerto Rico’s Rescued Schools: a grassroots adaptive reuse movement for abandoned school buildings. Social Sciences, 12(12), 662. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci12120662

5 essentials for the first 72 hours of disaster response. (2017, February 10). OCHA. https://www.unocha.org/publications/report/world/5-essentials-first-72-hours-disaster-response

Martinez, M. (2025, July 16). High prices, blackouts and half the money: Inside Puerto Rico’s stagnant food aid system. The 19th. https://www.msn.com/en-us/news/us/high-prices-blackouts-and-half-the-money-inside-puerto-rico-s-stagnant-food-aid-system/ar-AA1IHMSO

McGinley, K. A., Gould, W. A., Álvarez-Berríos, N. L., Holupchinski, E., & Díaz-Camacho, T. (2022). READY OR NOT? Hurricane preparedness, response, and recovery of farms, forests, and rural communities in the U.S. Caribbean. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 82, 103346. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2022.103346

Rivera Rivera, Y. (2024, February 23). Puerto Rico’s ‘Solidarity Supermarket’ Offers Fresh Local Food — and Dignity for Shoppers. Global Press Journal. https://globalpressjournal.com/americas/puerto-rico/puerto-ricos-solidarity-supermarket-offers-fresh-local-food-dignity-shoppers/

Nalley, A. (2025, August 29). Community Resilience Hubs: infrastructure that connects and protects. Southeast Sustainability Directors Network. https://www.southeastsdn.org/news/community-resilience-hubs/#:~:text=Now%2C%20as%20a%20functional%20resilience,resilience%20that%20pays%20for%20itself

RESILIENCE HUB MID-YEAR REPORT. (2022). https://www.vibranthawaii.org/_files/ugd/fb5ef8_48e6c7791ea24749b2f9a9670d537854.pdf

‘Resilience Hubs’ in Puerto Rico are vital in the wake of Hurricane Fiona. (2022, October). Mercy Corps. https://www.mercycorps.org/blog/resilience-hubs-puerto-rico-vital

Hartman, S. (2025, May 15). The 33 best crops for a High-Yield Survival Garden. Positivebloom. https://positivebloom.com/crops-for-high-yield-survival-garden/

Mattei, J., Borges-Méndez, R., & FDI Clinical Research. (2019). Agriculture and Food during a Natural Disaster. In Harvard TH Chan School of Public Health. https://content.sph.harvard.edu/wwwhsph/sites/391/2020/08/Community-report-English.pdf

American Academy of Pediatrics. (2007). Chapter 5: Facilities, Supplies, equipment, and Environmental health. In Standards from Caring for Our Children, 3rd Ed. https://marcheadstart.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/Resource-9010-Safe-Environments-CFOC-First-Aid-Kits.pdf

Rodríguez Cruz, L. A., & Niles, M. T. (2018). Hurricane Maria’s impacts on Puerto Rican farmers: Experience, challenges, and perceptions. Food Systems Program, The University of Vermont. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/333204111_Hurricane_Maria’s_Impacts_on_Puerto_Rican_Farmers_Experience_Challenges_and_Perceptions

Bea-Taylor, Jonah. 2022. “Getting the Lights Back On: The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Responds to Hurricane Maria, 2017-2018.” U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Digital Library. 2022. https://usace.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/p16021coll4/id/395/rec/11.

FEMA. 2018. “2017 Hurricane Season FEMA After-Action Report.” https://www.fema.gov/sites/default/files/2020-08/fema_hurricane-season-after-action-report_2017.pdf.